ffjson: faster JSON serialization for Golang

Published March 31st, 2014

ffjson is a project I have been hacking on for making JSON serialization faster in the Go programing language. ffjson works by generating static code for Go’s JSON serialization interfaces. Fast binary serialization frameworks like Cap’n Proto or Protobufs also use this approach of generating code. Because ffjson is serializing to JSON, it will never be as fast as some of these other tools, but it can beat the builtin encoding/json easily.

Benchmarks

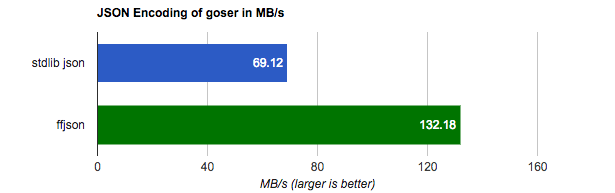

goser

The first example benchmark is Log structure that CloudFlare uses. CloudFlare open sourced these benchmarks under the cloudflare/goser repository, which benchmarks several different serialization frameworks.

Under this benchmark ffjson is 1.91x faster than encoding/json.

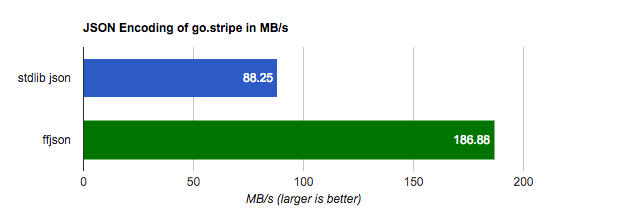

go.stripe

go.stripe contains a complicated structure for its Customer object which contains many sub-structures.

For this benchmark ffjson is 2.11x faster than encoding/json.

Try it out

If you have a Go source file named myfile.go, and your $GOPATH environment variable is set to a reasonable value, trying out ffjson is easy:

go get -u github.com/pquerna/ffjson

ffjson myfile.goffjson will generate a myfile_ffjson.go file which contains implementations of MarshalJSON for any structures found in myfile.go.

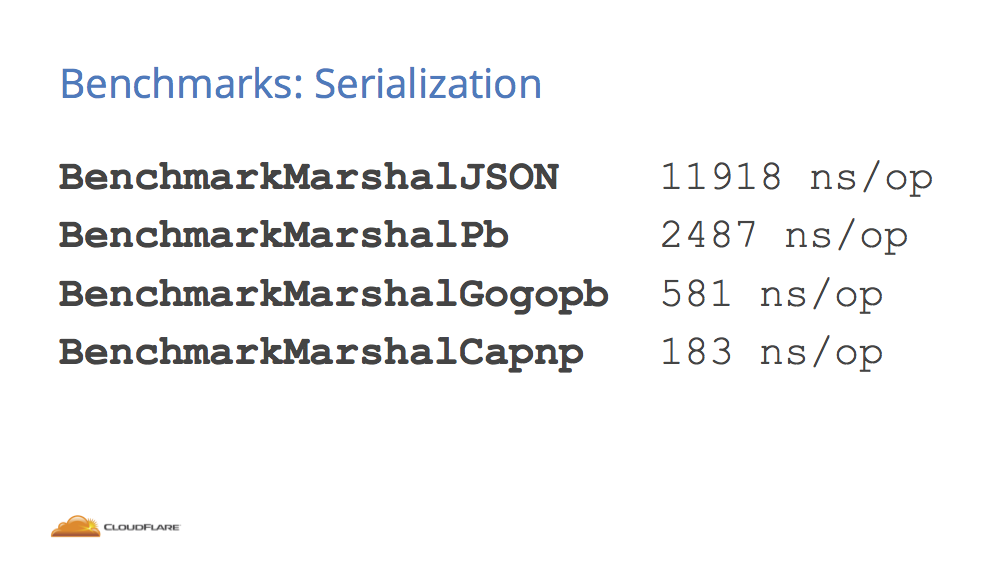

Background: Serialization @ GoSF

At the last GoSF meetup, Albert Strasheim from CloudFlare gave a presentation on Serialization in Go. The presentation was great — it showed how efficient binary serialization can be in Go. But what made me unhappy was how slow JSON was:

Why is JSON so slow in Go?

All of the competing serialization tools generate static code to handle data. On the other hand, Go’s encoding/json uses runtime reflection to iterate members of a struct and detect their types. The binary serializers generate static code for the exact type of each field, which is much faster. In CPU profiling of encoding/json it is easy to see significant time is spent in reflection.

The reflection based approach taken by encoding/json is great for fast development iteration. However, I often find myself building programs that serializing millions of objects with the same structure type. For these kinds of cases, taking a trade off for a more brittle code generation approach is worth the 2x or more speedup. The downside is when using a code generation based serializer, if your structure changes, you need to regenerate the code.

Last week we had a hack day at work, and I decided to take a stab at making my own code generator for JSON serialization. I am not the first person to look into this approach for Go. Ben Johnson created megajson several months ago, but it has limited type support and doesn’t implement the existing MarshalJSON interface.

Background: Leveraging existing interfaces

Go has an interface defined by encoding/json, which if a type implements, it will be used to serialize the type to JSON:

type Marshaler interface {

MarshalJSON() ([]byte, error)

}

type Unmarshaler interface {

UnmarshalJSON([]byte) error

}As a goal for ffjson I wanted users to get improved performance without having to change any other parts of their code. The easiest way to do this is by adding a MarshalJSON method to a structure, and then encoding/json would be able find it via reflection.

Example

The simplest example of implementing Marshaler would be something like the following, given a type Foo with a single member:

type Foo struct {

Bar string

}You could have a MarshalJSON like the following:

func (f *Foo) MarshalJSON() ([]byte, error) {

return []byte(`{"Bar":` + f.Bar + `}`), nil

}This example has many potential bugs, like .Bar not being escaped properly, but it would automatically be used by encoding/json, and avoids many reflection calls.

First Attempt: Using go/ast

During our hack day I started by using the go/ast module as a way to extract information about structures. This allowed rapid progress, and at my demo for the hack day I had a working prototype. This version was about 25% faster than encoding/json. However, I quickly found that the AST interface was too limiting. For example, a type is just represented as a simple string in the AST module. Determining if that type implements a specific interface is not easily possible. Because types are just strings to the AST module, complex types like map[string]CustomerType were up to me to parse by hand.

The day after the hack day I was frustrated with the situation. I started thinking about alternatives. Runtime reflection has many advantages. One of the most important is how easily you can tell what a type implements, and make code generation decisions based on it. In other languages you can do code generation at runtime, and then load that code into a virtual machine. Because Go is statically compiled, this isn’t possible. In C++ you could use templates for many of these types of problems too, but Go doesn’t have an equivalent. I needed a way to do runtime reflection, but at compile time.

Then I had an idea. Inception: Generate code to generate more code.

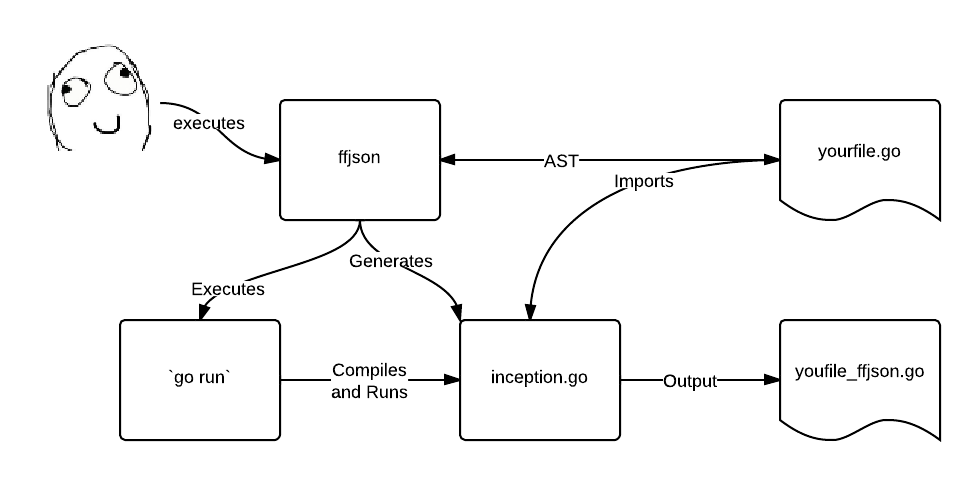

Inception

I wanted to keep the simple user experience of just invoking ffjson, and still generate static code, but somehow use reflection to generate that code. After much rambling in IRC, I conjoured up this workflow:

- User executes

ffjson ffjsonparses input file usinggo/ast. This decodes the package name and structures in the file.ffjsongenerates a temporaryinception.gofile which imports the package and structures previously parsed.ffjsonexecutesgo runwith the temporaryinception.gofile.inception.gouses runtime reflection to decode the users structures.inception.gogenerates the final static code for the structures.

It worked!

The inception approach worked well. The more powerful reflect module allowed deep introspection of types, and it was much easier to add support for things like Maps, Arrays and Slices.

Performance Improvements

After figuring out the inception approach, I spent some time looking for quick performance gains with the profiler.

Alternative Marshal interface

I observed poor performance on JSON structs that contained other structures. I found this to be because of the interface of MarshalJSON returns a []byte, which the caller would generally append to their own bytes.Buffer. I created a new interface that allows structures to append to a bytes.Buffer, avoiding many temporary allocations:

type MarshalerBuf interface {

MarshalJSONBuf(buf *bytes.Buffer) error

}This landed in PR#3, and increased performance by 18% for the goser structure. ffjson will use this interface on structures if it is available, if not it can still fall back to the standard interface.

FormatBits that works with bytes.Buffer

When converting a integer into a string, the strconv module has functions like AppendInt. These functions require a temporary []byte or a string allocation. By creating a FormatBits function that can convert integers and append them directly into a *bytes.Buffer, these allocations can be reduced or removed.

This landed in PR#5, and gave a 21% performance improvement for the goser structure.

What’s next for ffjson

I welcome feedback from the community about what they would like to see in ffjson. What exists now is usable, but I know there are few more key items to make ffjson great:

- Embedded Anonymous Structures:

ffjsondoesn’t currently handle embedded structures perfectly. I have a plan to fix it, I just need some time to implement it. - More real world structures for benchmarks: If you have an app doing high volume JSON, I would love to include an example in

ffjsonto highlight any performance problems with real world structures as much as possible. - Unmarshal Support: This will require writing a custom scanner/lexer, which is a larger project.

If you have any other ideas, I am happy to discuss them on the Github project page for ffjson

Written by Paul Querna, CTO @ ScaleFT. @pquerna