Evolution of Apache's websites

Published October 22nd, 2010

This is the story of Apache’s own websites. I believe they have seen an interesting evolution in complexity, user expectations, and growth the last 15 years. I use we in this article to describe the Apache Infrastructure team, a group of roughly 50 Apache committers over the last 15 years that run the servers that power the Apache Software Foundation.

Pre-history

A long time ago, on an internet far far away, the Apache Software Foundation had one server. Brian Behlendorf personally emailed you when your account was created. Using group file permissions, users were able to directly commit to a CVS repository on the machine that kept every projects source code history. The Apache website was just another folder on disk, and you just modified those files and the changes were live.

The Growth

In 2002, the Apache Incubator was created. This quickly lead to an explosion in the number of committers and projects inside the foundation. Each top level project had their own website content, their own downloads, and their own path in the CVS repository.

Apache started the migration to Subversion from CVS in 2003. One of the core values being created by the migration, was the elimination of the need of SSH/Shell access to commit code — since with Subversion, it was all done over HTTPS. At the same time, the number of top level projects increased as they began to graduate from the Incubator process.

At this time, the websites, version control, and shell accounts were still hosted on a single machine, minotaur.apache.org. There were a few other machines used for email, issue tracking, and builds, but whenever minotaur was down, everything at Apache would screech to a halt. This generation of Minotaur was a cobbled together server running FreeBSD 4 — Apache at the time didn’t have significant funding or donations to purchase servers itself.

The first rsync

As the Foundation grew, it became obvious there was an expectation for improved uptime in many services, and the public facing websites were something that should never be offline. In 2004 we added ajax.apache.org. Ajax was a donated HP Integrity rx5670, with 4x Intel Itanium processors and 12 gigabytes of RAM. Ajax was a beast compared to Apache’s previous servers, and even though Linux support of Itanium was relatively terrible, we got it all running.

As part of adding Ajax, we didn’t create accounts on it for all committers. Instead, we started using rsync to synchronize data from the shell server, Minotaur, and the production website server, Ajax. It worked. Every hour a crontab entry would fire, and copy any changes to Ajax. This was important because Minotaur had hundreds of shell accounts from all the different comitters, and it was impossible to prevent hundreds of random people from doing bad things.

The troubles with rsync

The basic pattern of an hourly rsync scaled quite well for several years. By now we had two frontend web server machines, both with hourly rsyncs over a hundred top level websites, and content approaching 400 gigabytes. Just scanning all of this data was becoming impossible in an hour period. This lead to several hours of delay between an edit on minotaur and it being made live.

An elegant, if terribly hacky solution was devised. Instead of running rsyncs over the entire filesystem containing the websites, a find command was created to detect changed files, based on their modified time. Every hour, this find command would run, finding all the files modified in the last few hours, and writing them to a file. Then we would run rsync, and only synchronize the files perviously found with find. We still ran a daily ‘full sync’, which took hours, and did things like delete files no longer present.

These changes massively reduced the load being placed on minotaur disk arrays, letting the number of sites and content continue to grow.

Getting Hacked

In August 2009, Apache.org was attacked. We changed many processes after the incident, but perhaps the most important impression was the difficulty in verifying terabytes of data and millions of files. If an attacker has access to a system for a period of days, and your existing users continue to modify the files along side them, it is very difficult and a time consuming process to determine what is a valid change.

We were saved by using ZFS snapshots in this incident, and without them it would of taken exponentially more time to validate our data. Filesystem snapshots are a crude method of versioning files, and at the same time our find+rsync file distribution method was beginning to strain. User expectations were also that changes should be made live quicker than ever before.

SvnPubSub experiments

After the hacking incident, the primary change we wanted was the ability to audit who, when and what changes are made to a filesystem. Most production Filesystems aren’t very good at these kind of requirements, so we turned to version control systems, which were designed exactly for this task.

Apache uses Subversion, and we have complete access control and authentication systems build around it, so the choice of version control systems was made. Instead of editing a file on disk, you edit a file in a version control system. Once committed, it is automatically synchronized to the production servers, within about 5 seconds. This gives the user instant feedback on changes, provides notification emails to the project with the change, and lets infrastructure move machines and websites around easily, knowing that their entire contents are stored in a specific path in version control.

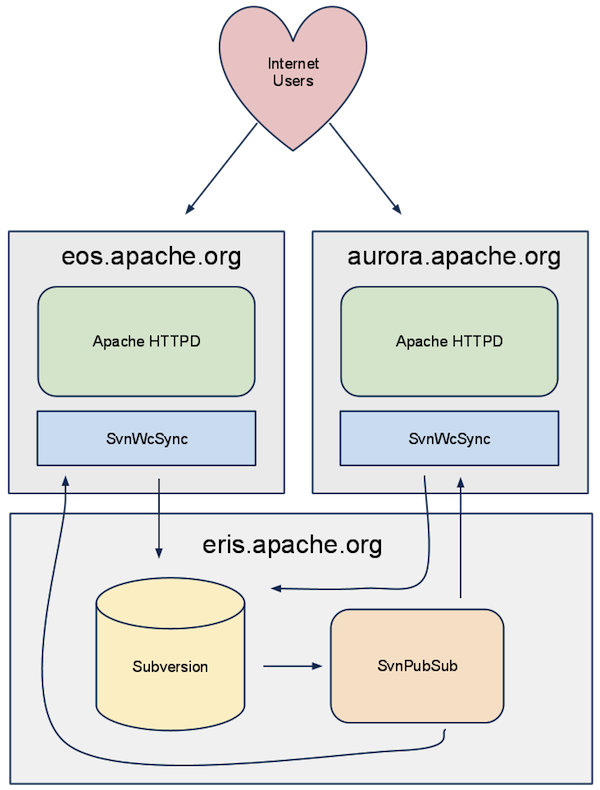

SvnPubSub is an HTTP server written in Twisted Python. It listens for change notifications, and publishes several streaming JSON or XML APIs with data about the change. SvnWcSub is the other component, which connects to these streaming APIs of changes, and then runs a glorified svn update on the local filesystem when the repository changes.

Using these tools, we built a system of near instant cross-atlanatic and reliable file replication. Compared to our previous metods of abusing rsync, synchronizing data with Subversion is a huge step forward. In addition, because it uses Subversion as its backing store, it is very easy to audit changes, and projects get increased visibility into changes on their own websites.

Data is committed to the Subversion repository by a committer, and a post commit hook notifies the SvnPubSub server running on eris.apache.org. The SvnPubSub server emits an event on its XML streams, which a SvnWcSub process on each web server is listening for. These SvnWcSub processes decide if the change affects one of the websites we are serving, and if so update their working copies. Internet users then instantly see the updated content.

We started developing this technique within days of the hacking incident. Today about 13, out of approximately 100 ASF project websites are synchronized using SvnPubSub. We expect this number to continue to grow as time goes on. I personally think in the next year or two, we will deprecate the rsync method of site synchronization, as it continues to have performance problems, and we will never be able to overcome the auditability concerns.

Apache CMS development

Apache’s websites have almost entirely been made up of static HTML. The times of everyone enjoying editing XML and HTML documents has passed on the larger internet, and the Foundation has grown to include less technical editors of the content. Many projects have used the Confluence Wiki as their CMS, and then exported the content to static HTML, but the plugin to do html exports has been unmaintained, and the change notifications very difficult to read.

We have been evaluating possible content management software for several years, but have not been happy with any of the possible solutions so far. Apache still runs all of our websites out of one live server, doing millions of hits per day, without even switching to nginx (A shock to the Web 3.0 crowd, I’m sure). If we used dynamic technologies like Drupal or Django, we would have to increase our server footprint, which has been frowned upon as a costly adventure in both machines and the time sink for system administrators, which today are still mostly volunteers.

This has lead to the decision to build a new CMS at Apache.

The complete rational for it is explained in this document. To keep up with the times, it is using NoSQL as its primary datastore. Subversion was selected for the NoSQL solution, because it provides great master-slave replication and versioning of a documents content. The new CMS uses Markdown as its primary document format, with templates around the markdown being written in a Perl implementation of DTL. Since the CMS stores the resulting HTML directly into Subversion, we are using our existing SvnPubSub infrastructure to replicate the websites across geographically diverse locations.

Coding started in early September of this year, and the CMS is still in development. Joe Schaefer wrote most of the code, and other committers have helped out with conversion of our documents from XML to Markdown. The CMS isn’t complete, but Apache Comitters can take the CMS for a spin. It is of course open source, and you can take a look at it inside the Infrastructure repository here. The goal was to have a usable system to power the www.apache.org site by ApacheCon, which is only a week away, and the goal has mostly been accomplished.

By keeping the CMS’s scope small, trying to build it up like a Unix tool, a new CMS has been born in just 2 months. It already is doing things no existing CMS could do, with Subversion as the primary data store, and it’s features continue to grow quickly. Hopefully once it reaches a more stable point, we can look at taking the CMS and making it a real Apache Project, rather than a infrastructure tool it is today.

Written by Paul Querna, CTO @ ScaleFT. @pquerna